Laozi

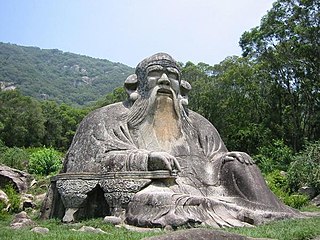

Laozi (/ˈlaʊdzə/, Chinese: 老子), also romanized as Lao Tzu and various other ways, was a semi-legendary ancient Chinese philosopher, author of the Tao Te Ching, the foundational text of Taoism along with the Zhuangzi. Laozi is a Chinese honorific, typically translated as "the Old Master". Modern scholarship generally regards his biographical details as invented, and his opus a collaboration. Traditional accounts say he was born as Li Er in the state of Chu in the 6th century BC during China's Spring and Autumn period, served as the royal archivist for the Zhou court at Wangcheng (in modern Luoyang), met and impressed Confucius on one occasion, and composed the Tao Te Ching in a single session before retiring into the western wilderness.

For the book also known as Laozi, see Tao Te Ching.

- Laozi

- 老子

- Laozi

- 老子

Trad. 5th century BC

Lǎozǐ

- the Old Master

- or

- the Old One

Lǎozǐ

Lǎozǐ

ㄌㄠˇ ㄗˇ

Laotzyy

Lao3-tzu3

Lǎo-zǐh

Lǎudž

Lâ-tsỳ

Lóuhjí

lou5 zi2

Ló-chú

Ló-tsú

Lǐ Ěr

Lǐ Ěr

Lǐ Ěr

Li3 Erh3

Lǐ Ěr

Lǐ Bóyáng

Lǐ Bóyáng

Lǐ Bóyáng

ㄌㄧˇ ㄅㄛˊ ㄧㄤˊ

Li3 Po2-yang2

Lǐ Bó-yáng

- Lǐ Dān

- Lǎo Dān

- Lǐ Dān

- Lǎo Dān

- Lǐ Dān

- Lǎo Dān

- ㄌㄧˇ ㄉㄢ

- ㄌㄠˇ ㄉㄢ

- Li3 Tan1

- Lao3 Tan1

- Lǐ Dan

- Lǎo Dan

Lǎojūn

the Old Lord

Lǎojūn

Lǎojūn

ㄌㄠˇ ㄐㄩㄣ

Lao3-chün1

Lǎo-jyun

老子

ろうし

ロウシ

Rōshi

Rōshi

Rousi

A central figure in Chinese culture, Laozi is generally considered the founder of Taoism. He was claimed and revered as the ancestor of the 7th–10th century Tang dynasty and is similarly honored in modern China as the progenitor of the popular surname Li. In some sects of Taoism, Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, and Chinese folk religion, it is held that he then became an immortal hermit.[2] Certain Taoist devotees held that the Tao Te Ching was the avatar – embodied as a book – of the god Laojun, one of the Three Pure Ones of the Taoist pantheon, though few philosophers believe this.[3] The Tao Te Ching had a profound influence on Chinese religious movements and on subsequent Chinese philosophers, who annotated, commended, and criticized the texts extensively. In the 20th century, textual criticism by modern historians led to theories questioning Laozi's timing or even existence, positing that the received text of the Tao Te Ching was not composed until the 4th century BC Warring States period, and was the product of multiple authors.

Name[edit]

Laozi /ˈlaʊdzə/ is the modern pinyin romanization of 老子. It is not a personal name, but rather an honorific title, meaning 'old' or 'venerable'. Its structure matches that of other ancient Chinese philosophers, such as Kongzi, Mengzi, and Zhuangzi.[4]

Traditional accounts give Laozi the personal name Li Er (李耳, Lǐ Ěr), whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *C.rəʔ C.nəʔ.[1] Li is a common Chinese surname meaning 'plum' or plum tree; there is a legend tying Laozi's birth to a plum tree.[5] Laozi has long been identified with the persona Lao Dan (老聃, Lǎo Dān).[6][7][8] Dan similarly means "Long-Ear" or "the Long-Eared One". The character 耳 is the Chinese word for 'ear'.[9]

Laozi is recorded bearing the courtesy name Boyang (伯陽, Bóyáng), whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *pˤrak laŋ.[1] The character 伯 was the title of the eldest son born to the primary wife, or an uncle of the father's family who was older than one's father, also used as a noble title indicating an aristocratic lineage head with rulership over a small to medium domain, and as a general mark of respect. The character 陽 is yang, the solar and masculine life force in Taoist belief. Lao Dan seems to have been used more generally, however, including by Sima Qian in his Records of the Grand Historian,[10] in the Zhuangzi,[10] and by some modern scholars.[11]

The Tao Te Ching is one of the most significant treatises in Chinese cosmogony. It is often called the Laozi, and has always been associated with that name. The identity of the person or people who wrote or compiled the text has been the source of considerable speculation and debate throughout history.[30][31] As with many works of ancient Chinese philosophy, ideas are often explained by way of paradox, analogy, appropriation of ancient sayings, repetition, symmetry, rhyme, and rhythm. The Tao Te Ching stands as an exemplar of this literary form.[32] Unlike most works of its genre, the book conspicuously lacks a central "master" character and seldom references historical people or events, giving it an air of timelessness.[33]

The Tao Te Ching describes the Tao as the source and ideal of all existence: it is unseen, but not transcendent, immensely powerful yet supremely humble, being the root of all things. People have desires and free will (and thus are able to alter their own nature). Many act "unnaturally", upsetting the natural balance of the Tao. The Tao Te Ching intends to lead students to a "return" to their natural state, in harmony with Tao.[34] Language and conventional wisdom are critically assessed. Taoism views them as inherently biased and artificial, widely using paradoxes to sharpen the point.[35]

Wu wei, literally 'non-action' or 'not acting', is a central concept of the Tao Te Ching. The concept of wu wei is multifaceted, and reflected in the words' multiple meanings, even in English translation; it can mean "not doing anything", "not forcing", "not acting" in the theatrical sense, "creating nothingness", "acting spontaneously", and "flowing with the moment".[36]

This concept is used to explain ziran, or harmony with the Tao. It includes the concepts that value distinctions are ideological and seeing ambition of all sorts as originating from the same source. Tao Te Ching used the term broadly with simplicity and humility as key virtues, often in contrast to selfish action. On a political level, it means avoiding such circumstances as war, harsh laws and heavy taxes. Some Taoists see a connection between wu wei and esoteric practices, such as zuowang ('sitting in oblivion': emptying the mind of bodily awareness and thought) found in the Zhuangzi.[35]

Alan Chan provides an example of how Laozi encouraged a change in approach, or return to "nature", rather than action. Technology may bring about a false sense of progress. The answer provided by Laozi is not the rejection of technology, but instead seeking the calm state of wu wei, free from desires. This relates to many statements by Laozi encouraging rulers to keep their people in "ignorance", or "simple-minded". Some scholars insist this explanation ignores the religious context, and others question it as an apologetic of the philosophical coherence of the text. It would not be unusual political advice if Laozi literally intended to tell rulers to keep their people ignorant. However, some terms in the text, such as "valley spirit" (谷神, gushen) and 'soul' (魄, po), bear a metaphysical context and cannot be easily reconciled with a purely ethical reading of the work.[35]