Western painting

The history of Western painting represents a continuous, though disrupted, tradition from antiquity until the present time.[1] Until the mid-19th century it was primarily concerned with representational and traditional modes of production, after which time more modern, abstract and conceptual forms gained favor.[2]

Initially serving imperial, private, civic, and religious patronage, Western painting later found audiences in the aristocracy and the middle class. From the Middle Ages through the Renaissance painters worked for the church and a wealthy aristocracy.[3] Beginning with the Baroque era artists received private commissions from a more educated and prosperous middle class.[4] The idea of "art for art's sake"[5] began to find expression in the work of the Romantic painters like Francisco de Goya, John Constable, and J. M. W. Turner.[6] During the 19th century commercial galleries became established and continued to provide patronage in the 20th century.[7][8]

Western painting reached its zenith in Europe during the Renaissance, in conjunction with the refinement of drawing, use of perspective, ambitious architecture, tapestry, stained glass, sculpture, and the period before and after the advent of the printing press.[9] Following the depth of discovery and the complexity of innovations of the Renaissance, the rich heritage of Western painting continued from the Baroque period to Contemporary art.[10]

The history of painting reaches back in time to artifacts from pre-historic artists, and spans all cultures. The oldest known paintings are at the Grotte Chauvet in France, claimed by some historians to be about 32,000 years old. They are engraved and painted using red ochre and black pigment and show horses, rhinoceros, lions, buffalo, mammoth, or humans often hunting.

Prehistoric European cave paintings share common themes with other prehistoric paintings that have been found throughout the world; implying the universality of purpose and similarity of the impulses that might have inspired the artists to create the imagery. Various conjectures have been made as to the meaning these paintings had to the artists who made them. Prehistoric men may have painted animals to "catch" their soul or spirit in order to hunt them more easily, or the paintings may represent an animistic vision and homage to surrounding nature, or they may be the result of a basic need of expression that is innate to human beings, or they may be recordings of the life experiences of the artists and related stories from the members of their circle.

The rise of Christianity imparted a different spirit and aim to painting styles. Byzantine art, once its style was established by the 6th century, placed great emphasis on retaining traditional iconography and style, and gradually evolved during the thousand years of the Byzantine Empire and the living traditions of Greek and Russian Orthodox icon-painting. Byzantine painting has a hieratic feeling and icons were and still are seen as a representation of divine revelation. There were many frescos, but fewer of these have survived than mosaics.

Byzantine art has been compared to contemporary abstraction, in its flatness and highly stylised depictions of figures and landscape. Some periods of Byzantine art, especially the so-called Macedonian art of around the 10th century, are more flexible in approach. Frescoes of the Palaeologian Renaissance of the early 14th century survive in the Chora Church in Istanbul.

In post-Antique Catholic Europe the first distinctive artistic style to emerge that included painting was the Insular art of the British Isles, where the only surviving examples are miniatures in Illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells.[20] These are most famous for their abstract decoration, although figures, and sometimes scenes, were also depicted, especially in Evangelist portraits. Carolingian and Ottonian art also survives mostly in manuscripts, although some wall-painting remain, and more are documented. The art of this period combines Insular and "barbarian" influences with a strong Byzantine influence and an aspiration to recover classical monumentality and poise.

Walls of Romanesque and Gothic churches were decorated with frescoes as well as sculpture and many of the few remaining murals have great intensity, and combine the decorative energy of Insular art with a new monumentality in the treatment of figures. Far more miniatures in Illuminated manuscripts survive from the period, showing the same characteristics, which continue into the Gothic period.

Panel painting becomes more common during the Romanesque period, under the heavy influence of Byzantine icons. Towards the middle of the 13th century, Medieval art and Gothic painting became more realistic, with the beginnings of interest in the depiction of volume and perspective in Italy with Cimabue and then his pupil Giotto. From Giotto on, the treatment of composition by the best painters also became much more free and innovative. They are considered to be the two great medieval masters of painting in western culture. Cimabue, within the Byzantine tradition, used a more realistic and dramatic approach to his art. His pupil, Giotto, took these innovations to a higher level which in turn set the foundations for the western painting tradition. Both artists were pioneers in the move towards naturalism.

Churches were built with more and more windows and the use of colorful stained glass become a staple in decoration. One of the most famous examples of this is found in the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. By the 14th century Western societies were both richer and more cultivated and painters found new patrons in the nobility and even the bourgeoisie. Illuminated manuscripts took on a new character and slim, fashionably dressed court women were shown in their landscapes. This style soon became known as International Gothic style and was dominant from 1375 to 1425 with and tempera panel paintings and altarpieces gaining importance.

After Rococo there arose in the late 18th century, in architecture, and then in painting severe neo-classicism, best represented by such artists as David and his heir Ingres. Ingres' work already contains much of the sensuality, but none of the spontaneity, that was to characterize Romanticism.

By the mid-19th century, painters became liberated from the demands of their patronage to only depict scenes from religion, mythology, portraiture or history. Art became more purely a means of personal expression in the work of painters like Francisco de Goya, John Constable, and J. M. W. Turner. Romantic painters turned landscape painting into a major genre, considered until then as a minor genre or as a decorative background for figure compositions.

Some of the major painters of this period are Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Géricault, J. M. W. Turner, Caspar David Friedrich and John Constable. Francisco Goya's late work demonstrates the Romantic interest in the irrational, the work of Arnold Böcklin evokes mystery, the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England combines assiduous devotion to nature with nostalgia for medieval culture, and the paintings of Aesthetic movement artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler evoke sophistication, decadence, and the philosophy of "art for art's sake". In the United States the Romantic tradition of landscape painting was known as the Hudson River School:[27] exponents include Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, and John Frederick Kensett. Luminism was a movement in American landscape painting related to the Hudson River School.

A major force in the turn towards Realism at mid-century was Gustave Courbet, whose unidealized paintings of common people offended viewers accustomed to the conventional subject matter and licked finish of academic art, but inspired many younger artists. The leading Barbizon School painter Jean-François Millet also painted landscapes and scenes of peasant life. Loosely associated with the Barbizon School was Camille Corot, who painted in both a romantic and a realistic vein; his work prefigures Impressionism, as did the paintings of Johan Jongkind and Eugène Boudin (who was one of the first French landscape painters to paint outdoors). Boudin was an important influence on the young Claude Monet, whom in 1857 he introduced to plein air painting.

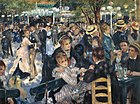

In the latter third of the century Impressionists such as Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, and Edgar Degas worked in a more direct approach than had previously been exhibited publicly. They eschewed allegory and narrative in favor of individualized responses to the modern world, sometimes painted with little or no preparatory study, relying on deftness of drawing and a highly chromatic palette. Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley used the landscape as their primary motif, the transience of light and weather playing a major role in their work. Following a practice that had become increasingly popular by mid-century, they often ventured into the countryside together to paint in the open air, but not for the traditional purpose of making sketches to be developed into carefully finished works in the studio.[28] By painting in sunlight directly from nature, and making bold use of the vivid synthetic pigments that had become available since the beginning of the century, they developed a lighter and brighter manner of painting.

Manet, Degas, Renoir, Morisot, and Cassatt concentrated primarily on the human subject. Both Manet and Degas reinterpreted classical figurative canons within contemporary situations; in Manet's case the re-imaginings met with hostile public reception. Renoir, Morisot, and Cassatt turned to domestic life for inspiration, with Renoir focusing on the female nude. While Sisley most closely adhered to the original principals of the Impressionist perception of the landscape, Monet sought challenges in increasingly chromatic and changeable conditions, culminating in his series of monumental works of Water Lilies painted in Giverny.

Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne and the slightly younger Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Georges-Pierre Seurat led art to the edge of modernism. For Gauguin Impressionism gave way to a personal symbolism. Seurat transformed Impressionism's broken color into a scientific optical study, structured on frieze-like compositions. The painting technique he developed, called Divisionism, attracted many followers such as Paul Signac, and for a few years in the late 1880s Pissarro adopted some of his methods. Van Gogh's turbulent method of paint application, coupled with a sonorous use of color, predicted Expressionism and Fauvism, and Cézanne, desiring to unite classical composition with a revolutionary abstraction of natural forms, would come to be seen as a precursor of 20th-century art.

The spell of Impressionism was felt throughout the world, including in the United States, where it became integral to the painting of American Impressionists such as Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and Theodore Robinson. It also exerted influence on painters who were not primarily Impressionistic in theory, like the portrait and landscape painter John Singer Sargent. At the same time in America at the turn of the 20th century there existed a native and nearly insular realism, as richly embodied in the figurative work of Thomas Eakins, the Ashcan School, and the landscapes and seascapes of Winslow Homer, all of whose paintings were deeply invested in the solidity of natural forms. The visionary landscape, a motive largely dependent on the ambiguity of the nocturne, found its advocates in Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Albert Blakelock.

In the late 19th century there also were several, rather dissimilar, groups of Symbolist painters whose works resonated with younger artists of the 20th century, especially with the Fauvists and the Surrealists. Among them were Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Henri Fantin-Latour, Arnold Böcklin, Ferdinand Hodler, Edvard Munch, Félicien Rops, Jan Toorop, and Gustav Klimt, and the Russian Symbolists such as Mikhail Vrubel.

Symbolist painters mined mythology and dream imagery for a visual language of the soul, seeking evocative paintings that brought to mind a static world of silence. The symbols used in Symbolism are not the familiar emblems of mainstream iconography but intensely personal, private, obscure and ambiguous references. More a philosophy than an actual style of art, the Symbolist painters influenced the contemporary Art Nouveau movement and Les Nabis. In their exploration of dreamlike subjects, symbolist painters are found across centuries and cultures, as they are still today; Bernard Delvaille has described René Magritte's surrealism as "Symbolism plus Freud".[29]

On the effects of Gutenberg's printing

![Roman glass with a painted figure of a gladiator, found at Begram, Afghanistan (once part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, then under the Kushan Empire), 52–125 AD[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Gladiateur_Begram_Guimet_18117.jpg/97px-Gladiateur_Begram_Guimet_18117.jpg)

![Henri Rousseau, 1905, the reason for the term Fauvism] and the original "Wild Beast"](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Rousseau-Hungry-Lion.jpg/140px-Rousseau-Hungry-Lion.jpg)